Vaccine Dezinformatsiya

Should you spend time arguing with the anti-vaccine lobby on the internet? After all, someone is always wrong on the internet and duty calls.

A paper analysing a retrospective set of 1.8 million tweets suggests caution is required.1 David Broniatowski and colleagues examined vaccine-related tweets in this sample, and compared how normal users posted vaccine messages compared to trolls and bots. Trolls and bots produced vaccine material more often than normal users, creating conflict amongst other users and disinformation. Much of this material was sourced from Russia.

The use of disinformation, or as the Russians call it dezinformatsiya, is not new. Soviet disinformation started back in the 1920s, and continued throughout the Cold War. After the end of the Cold War, it found new life under Putin and his troll Factories.

“The term dezinformatsiya denoted a variety of techniques and activities to purvey false or misleading information that Soviet bloc active measures specialists sought to leak into the foreign media. From the Western perspective, disinformation was a politically motivated lie, but Soviet bloc propagandists believed their disinformation campaigns merely highlighted greater truths by exposing the real nature of capitalism.”

Dezinformatsiya is less about the evils of capitalism these days, and more about Russian nationalism. Modern day disinformation attempts include provocation for regime change in Montenegro, spinning concern about suspected Russian chemical attacks on the UK as hate speech against Russia, and accusing Finland of putting Russian children in prison. That’s before you even get to the Russian involvement in the 2016 US Presidential election, and the Brexit referendum.

Russian attempts to create discord and polarisation are endemic. In the case of the Ukraine, the use of disinformation was a key component of the Russian annexation of the Crimea, and the continuing separatist narrative in the Ukraine. If there is fracture in your society, the Russians will be there prying at it, handing out free icepicks to those willing to lend a hand. They have had great success.

In 2016 in the US they even managed to organise a real world Black Lives Matter protest using Facebook, and in an act of genius also organised the counter-protest against it. In 2017, a photograph of a Muslim lady walking past victims of a terrorist attack (malignly characterised as uncaring) in the UK was widely circulated and commented on in a very polarised debate.

The provenance of the initial tweet creating a maelstrom on social media that eventually broke through to mainstream media?

The ensuring outrage, from those with good and bad intentions, served the bot’s intention to spread the disinformation wider. Russian disinformation often seeks to create debates on race or immigration in order to destabilise the political establishment in Europe and the US. This echoes old Soviet tactics. That pro-Russian populists, of the far right and far left, may benefit from this is not a surprise.

Russian disinformation is a complex operation, ranging from so-call troll farms to bots, the twitter feeds of their official embassies, to Russian funded media such as Sputnik or Russia Today. The latter has a veneer of respectability, with political figures, including the current leader of the UK opposition, willing to appear as guests.

To counter Russian dezinformatsiya, Europe set up a Task Force to counter the threat. Their website EU vs Disinfo states they have had 3800 disinformation cases from September 2015 to Spring of 2018, and provides numerous examples of recent disinformation, including disinformation on health issues, such as vaccination.

One of the worst cases cases of disinformation related to health occurred at the tail end of the Cold War. The Soviets sought to exploit the HIV/AIDs crisis in Operation Infektion.2 In 1983, a letter, almost certainly written by the KGB, was published in an Indian magazine suggesting that HIV had been developed by the US government. Disinformation was created and planted outside of Russia, and then built on. The KGB were experts in exploiting real concerns, such as the Tuskegee experiment, and converting them into wider conspiracies. Over the remainder of the 1980s the story was amplified through various media outlets, eventually outliving the KGB use of the conspiracy. A survey in 2005, found 50% of African Americans believed HIV was man-made, with over 25% believing it had been made in a government lab. In sub-sharan Africa, the conspiracy mutated, leading to suggestions of “AIDS-oiled” condoms from the US, and Robert Mugabe calling AIDs a “white man’s plot.”

Similarly, modern day anti-vaccine material can also cause harm. In Europe more than 41,000 people have been infected with measles in the first six months of 2018, leading to 37 deaths. Pushing anti-vaccine propaganda has a price. Now disinformation can be planted directly into social media feeds of populations. There is evidence that more emotional or moral tweets are interacted with more in twitter, so it is no surprise to find that many of the tweets found by Broniatowski et al1 are designed to be more provocative in nature, including racial, ethic and socio-economic issues:

“#VaccinateUS messages included several distinctive arguments that we did not observe in the general vaccine discourse. These included arguments related to racial/ethnic divisions, appeals to God, and arguments on the basis of animal welfare. These are divisive topics in US culture, which we did not see frequently discussed in other tweets related to vaccines. For instance, “Apparently only the elite get ‘clean’#vaccines. And what do we, normal ppl, get?! #VaccinateUS” appears to target socioeconomic tensions that exist in the United States. By contrast, standard antivaccine messages tend to characterize vaccines as risky for all people regardless of socioeconomic status”

The accounts also posted pro-vaccine messages. The intention of trolls was to keep the discussion going. Human users would be retweeted by the troll accounts, so benign pro-vaccine messages by non-trolls would feed the trolls “giving the false impression of legitimacy to both sides”. The paper contains an argument that that reducing pro-vaccination tweets in these engagements might lead to overall less anti-vaccine content becoming visible, and that public health messages need to be carefully crafted to avoid strengthening such anti-vaccine material.

However, it is a game that many will still play. People with the best of intentions will feed the trolls. Just knowing that the game exists is a start though.

-

David A. Broniatowski et al. “Weaponized Health Communication: Twitter Bots and Russian Trolls Amplify the Vaccine Debate”, American Journal of Public Health. 2018: DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304567 ↩ ↩2

-

Boghardt T. Operation INFEKTION: Soviet Bloc Intelligence and Its AIDS Disinformation Campaign. Studies in Intelligence. 2009;53(4):1-24 PDF ↩

It's not about the vaccines.

Communicating the positive harm-benefit of vaccines is complex. Vaccination scares cause real harm. As one example, let’s take measles vaccination.

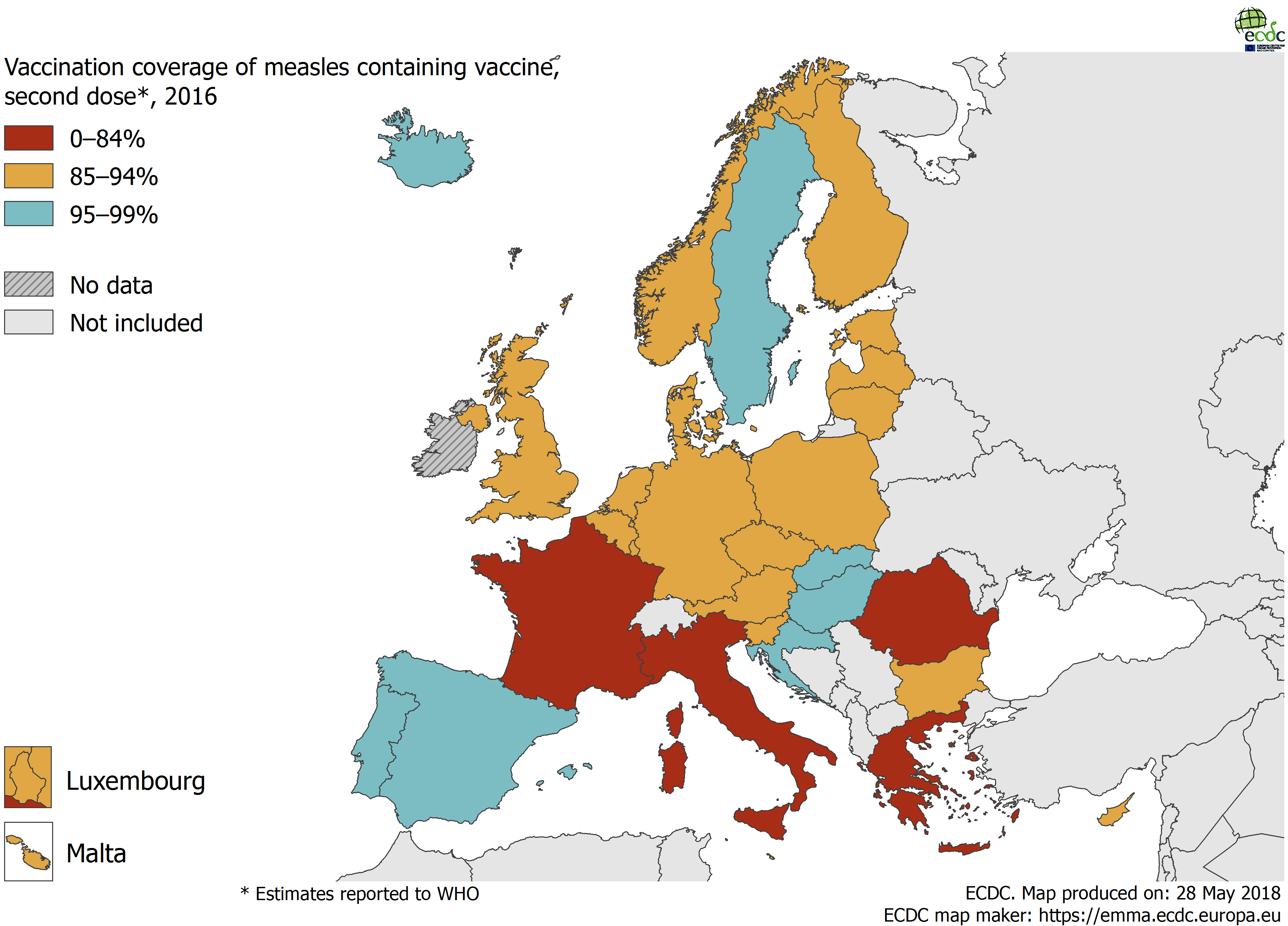

Vaccination with measles occurs through the administration of MMR vaccine. Vaccination rates in many European states do not provide herd immunity against measles.

Data from [The European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention](https://ecdc.europa.eu/).

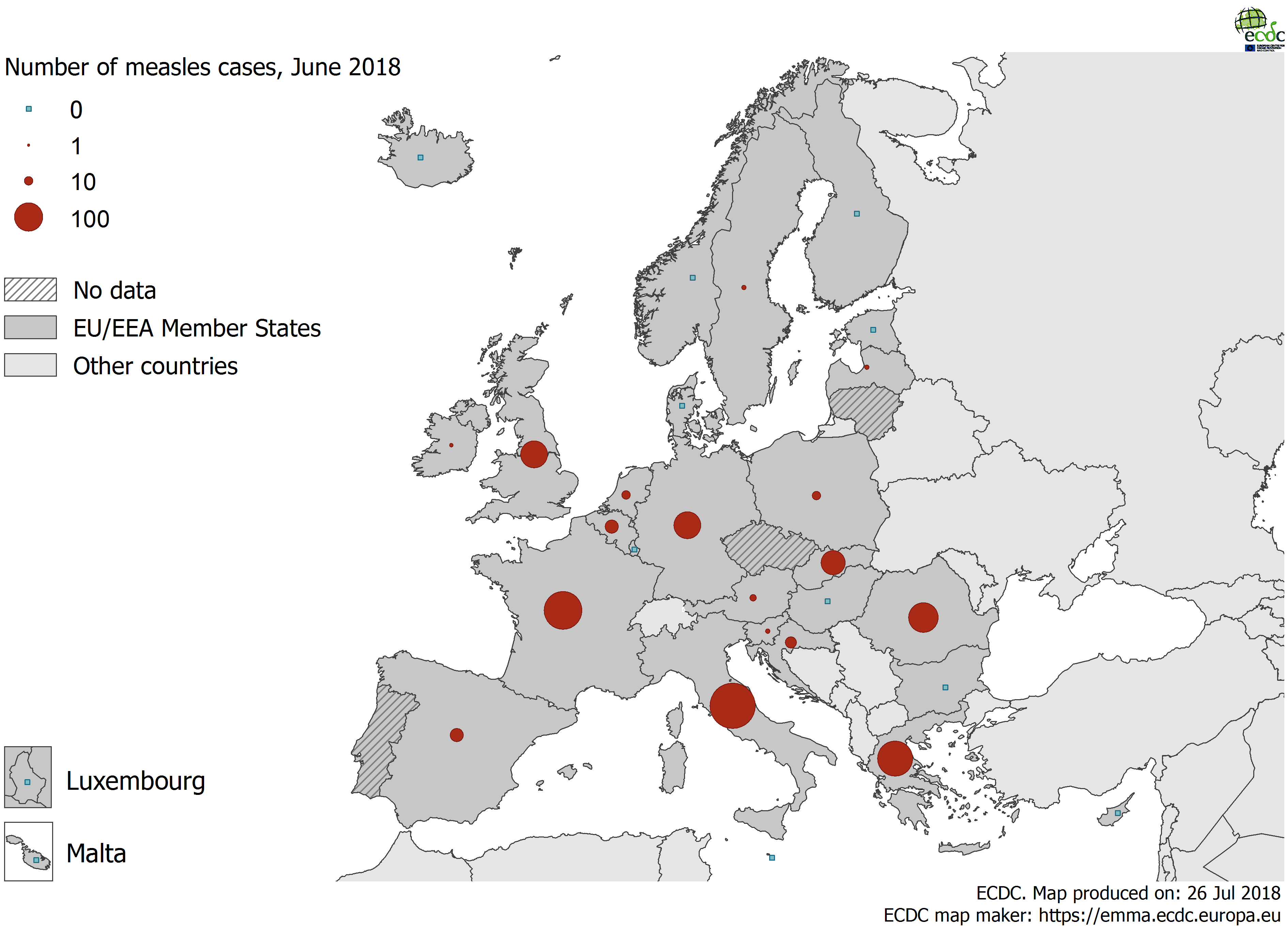

This leads to measles outbreaks across Europe, and preventable deaths of children (21 in Europe from May 2017-April 2018). Here’s the data for measles cases in June 2018 alone in Europe.

The reasons for the failure to vaccinate against measles are multi-factorial, and anti-vaccine views have existed since vaccination was invented. However, one of the drivers for falls in vaccination worldwide were the unfounded fears that autism was linked to MMR vaccine use. Wakefield, the originator of this hoax safety concern, was eventually proven wrong. Yet, fears have remained, and have travelled worldwide, and his false science echoes on.

The major period of Wakefield’s scare stories overlapped with the rise in the use of the internet, yet were mainly based in print, television, and radio media. Blogs and forums were part of the debate (pro and anti), and there were government websites to promote vaccine safety in the UK, but old media was still relatively strong.

When the scientific community was trying to prove Wakefield’s hypothesis wrong, attempts to communicate the findings of studies were a double edged sword. Sure, you might have a study that showed no higher rates of autism in children given MMR vaccine, but often it might just re-open the debate about the safety of the vaccine: another cycle of articles casting doubt on the vaccine and more radio call in shows. The news might say “Study shows no association of MMR vaccine with autism”, but nervous parents would just see ”Study shows no association of MMR vaccine with autism.”

One might have hoped that social media and smart phones would improve communications about vaccines. Instead, In politics it has polarised debate. Facts are chosen by how much they align with our tribal stance, than with reality. Extreme emotive views get more traction on social media. Loud noisy extremists get more attention than calm rationalists. The same occurs with anti-vaccinators. Incorrect information can be propagated quickly, usually further than any correction ever goes. Views will be reenforced. Vaccine facts may remain in the bubble of science-based individuals, with little overlap into the communities that need the information.

Gesualdo et al (2018) suggest in an article called “To talk better about vaccines, we should talk less about vaccines” that the focus should move away from vaccines to vaccines’ impact. After discussing the relative ineffectiveness of debunking incorrect vaccine stories, and noting that numbers do not change behaviours, they call for a move away from data provision to addressing emotional needs:

What would happen if we stopped inviting the public to rationally concentrate on data, and rather stimulated their emotions through positive messages?

The image of a child can evoke a sense of vulnerability. The image of a sick person can evoke fear and anguish. The story of an adult that has accomplished his or her dreams - thanks (also) to vaccines, that have allowed for a healthy growth - has the power of evoking a sense of strength, a positive value.

We should start focusing on how vaccines impact on a person’s life, not exclusively in clinical terms, but through the invisible values they generate.

This would fit with Jonathan Haidt’s view1 that humans are emotional beings first, who then use reason to justify the initial intuition, or as Hume put it “Reason is […] the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them”

Haidt’s analogy is that of an huge elephant, making gut decisions and intuitions to chose a path, and a rider employing reason on the back. The rider may coax the elephant into a change of direction, but elephants are large and hard to stop. Often, reason will be merely employed to justify the initial gut reaction of the elephant (for example, choosing only to examine data that supports the initial decision).

You can, of course, train your elephant. You may have intuitions about the safety of air travel, and use statistics on the safety of air travel to calm your elephant. No doubt some parents have been re-assured by data on vaccine safety, but is it so wrong to use emotion and positive messages about vaccines to get everyone’s elephant on the right track, in a herd?

Picture: “Sick girl at UNICEF-supported health center in Sam Ouandja refugee camp” by hdptcar.

-

*Haidt’s views are in a more accessible format in his two excellent books The Happiness Hypothesis, and The Righteous Mind. ↩

Running on NSAIDs.

The use of medicines always comes with risks, but your individual risk may vary based on your physiology, you gender, your genetics, and your behaviour. Although much of the focus on drug use in athletes concerns performance enhancement, drug use by athletes can be associated with risks even if not a performance enhancing drug.

Non Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen and diclofenac are widely used as painkillers. They are not banned by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), although some have argued they can increase performance. However, generally they are used by athletes to reduce pain from an injury, or to reduce pain in recovery after an event. Anyone who knows the running community, or who has spotted the used blister strips of NSAIDs on the floor at major marathons, will be aware of this.

The nature of some events, particularly long-distance endurance events, means that athletes might be more at risk of some adverse effects of NSAIDs. The physiological stress of running may make individuals more prone to gastro-intestinal problems, acute kidney damage, or hyponatraemia. Some athletes may also have pre-existing contra-indications, or cautions for use, that they are either ignorant of, or deliberately ignore.

We recently looked at the use of NSAIDs in three athletic clubs, that covered the three disciplines of running, cycling, and triathlon.1 We found high usage of oral NSAIDs (70%), more so in the more impact related sports of running and triathlon. Only a quarter of this use was informed by a pharmacist or a doctor, and the majority from over-the-counter sales. Nearly half of respondents used NSAIDs before or after an event. Some, worryingly, even take them during events.

That people are so ready to take NSAIDS for recovery, and to push through pain to complete events, is a concern. Even post event use, may delay the adaptive response to exercise and be counter-productive to the wider aims of the athlete. As with the wider concerns about NSAID use, the best bet is to avoid use if possible, but at least be aware of the risks you may be taking, particularly in longer endurance events.

Photograph: Start of the Paris Marathon 2011, Av. des Champs-Élysées, by Anthony Cox

Posts

-

Vaccine boost

-

Talking about vaccines

-

Communicating Vaccine Safety

-

Blood clot fears: how misapplication of the precautionary principle may undermine public trust in vaccines.

-

Human Factors Teaching: Using storytelling.

-

Electronic prescribing: Different professions, similar problems.

-

Medicines Safety Week: Special Medication Safety Edition of the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice

-

Medicines Safety Week: Finding Needles in Haystacks

-

World Patient Safety Day

-

Science Fictions

-

Ten Steps to Safety

-

Recreational running and NSAIDs

-

Shifting to online teaching, shouldn't mean being remote

-

The Power of Stories

-

The Importance of Patient Information

-

Cambridgeshire Methotrexate Toxicity Report

-

Shortages and Shifts

-

Medication Safety - Call for Papers

-

Brexit and Drug Shortages

-

Conformity and Pharmacovigilance

-

Deprescribing Culture

-

I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For.

-

Dynamic to static

-

Medicines Safety Week – Make a pledge, make a habit.

-

Rethinking multi-compartment compliance aids.

-

Vaccine Dezinformatsiya

-

It's not about the vaccines.

-

Running on NSAIDs.

subscribe via RSS