Conformity and Pharmacovigilance

In the recent Chernobyl TV series, the dangers of conformity were clearly demonstrated. Multiple times. Shortly after the explosion, the Pripyat Executive Committee meets. A member expresses concern about the dangers facing Pripyat. He is effectively silenced by the social cost of not conforming to the group, the power of a high-ranking Soviet official, and false reassurances of a nuclear expert. Pripyat was not evacuated.

The costs of conformity are apparent these days on social media, where “cancel culture” and “pile ons” are used to enforce norms (often for opinions that might be widely held and are uncontroversial in offline culture) leading to political polarisation. Neither do you have to have lived in the Soviet Union to have been in a meeting where items are not challenged, or useful information not proffered, because of the potential cost of being “wrong”. The net loss of information this causes has its own cost. The emperor will walk without clothes far longer, or in the case of drug safety, unsafe prescribing practice may continue unabated.

At the turn of the century it was a widely accepted view that hormone replacement therapy (HRT) conferred cardiovascular benefits. An expert speaker on an evidence-based medicine course I was running in the very early 2000s berated a paper that suggested that these effects were unlikely, Observational data and mechanisms were provided as to why the cardiovascular benefit was real. Everyone nodded. Later it was found that HRT did not confer a cardiovascular benefit in a randomised clinical trial and, in fact, inflicted a harm instead.1

Confounding was likely the cause in the observational studies. Women seeking HRT may have been unrepresentative of the general population, and less likely to develop cardiovascular disease. Was it the only cause though? The spread of the cardiovascular benefit of HRT amongst prescribers was widespread. Why do ideas become established, even when dissenting voices could challenge them? Cass Sunstein’s book on Conformity gives some clues.

Sunstein is a Professor at Harvard, who worked at the White House Office of Information and Regulatory affairs from 2009 to 2012, and was co-author of Nudge. His book is a concise journey through the psychology of conformity. Two key ideas start the book. The first, is that the actions and words of people around you are used as information to try to discern the truth. Secondly, what people do and say around you informs you how to behave to remain part of the group. Even if you have misgivings, you may suppress your views to remain part of the tribe.

Sunstein uses HRT as a example of how wrong information cascades. Rather than using privately held information, trusting their own judgement, prescribers will look at informational signals from other prescribers. A prescriber deciding whether or not to prescribe HRT for cardiovascular benefit will see other doctors have prescribed HRT, and unless they are extremely confident about their alternative view, they will prescribe it. The informational cascade of wrong information grows. None of the doctors may be confident about the evidence of a cardiovasular benefit of HRT. However, the uncertainity is kept private and the net effect is to show high confidence of benefit by virtue of the informational signals (prescribing) the prescribers send.

Such informational cascades can be broken, the change in views on opiate prescribing may be one recent example, but are still common. Sunstein also cites prostate-specific antigen (PSA) testing as another example. In the field of drug safety and pharmacovigilance, understanding how to break such informational cascades may be key to changing prescribing culture, once a risk has been identified. Certainly, the current track record of influencing prescribing decisions is mixed.2

This is only one aspect of the book; Sunstein provides a lens to view several current challenges in the world. Even at a more parochial level, for those want to make better group decisions with maximal information, and with less group think, the book provides useful information to engender an open culture to enable useful dissent.

Photograph The Corrosion of Conformity by Thomas Hawk. Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic

-

Writing Group for the Women’s Health Initiative Investigators. Risks and Benefits of Estrogen Plus Progestin in Healthy Postmenopausal Women: Principal Results From the Women’s Health Initiative Randomized Controlled Trial. _JAMA. 2002;288(3):321–333. doi:10.1001/jama.288.3.321 ↩

-

Barber C, Gagnon D, Fonda J et al. Assessing the impact of prescribing directives on opioid prescribing practices among Veterans Health Administration providers. Pharmacoepidemiology and Drug Safety. 2017;26(1):40-46 ↩

Deprescribing Culture

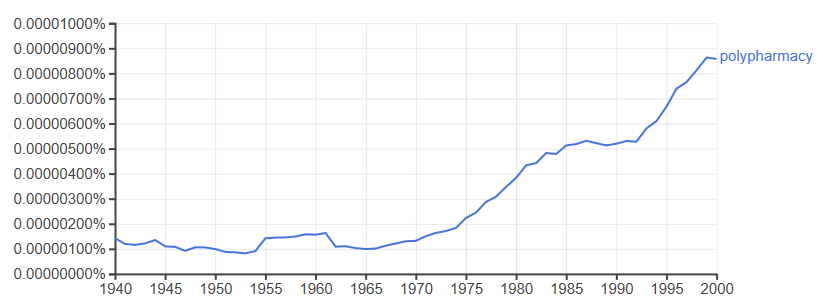

Inappropriate use of medicines is a longstanding problem; a Google ngram for polypharmacy shows it first appeared in 1843 and its usage quarupled in the second half of the 20th century.

Deprescribing has yet to appear on Google ngrams, but is highly prevalence on social media and in more recent academic work. One definition is:

Deprescribing is the process of withdrawal of an inappropriate medication, supervised by a health care professional with the goal of managing polypharmacy and improving outcomes.1

Deprescribing appears to have gained more traction than polypharmacy amongst practitioners. Perhaps because deprescribing does not merely describe the world, but seeks to change it. Invert the act of prescribing, and you give permission to act. A tribe of like-minded people are starting to change the culture. People are doing great work.2

Pharmaceutical marketing, single-disease state evidence based medicine guidelines, government targets, and socio-cultural expectations of treatment added to the problem of polypharmacy.3 Polypharmacy seemed insurmountable. You can try to build a movement on a problem, but a solution is better.

As a meme, deprescribing is an evolutionary shift of emphasis. A pivot. It’s not entirely new, anyone working as an enlightened clinical pharmacist back in the 1990s would have done some, but the stop(p)-start growth of concern about the burden of medicine harms, extension of clinical pharmacists into primary care, prescribing rights, and pharmacogenomics have given greater opportunities to make a difference.

But…

Could a single word change help change practice?

In the case of deprescribing, on balance, I think so.

-

Reeve E, Gnjidic D, Long J, Hilmer S. A systematic review of the emerging definition of ‘deprescribing’ with network analysis: implications for future research and clinical practice. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;80(6):1254–1268. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12732. LINK ↩

-

As one example, deprescribing.org is a great example. ↩

-

Amongst other things… ↩

I Still Haven't Found What I'm Looking For.

Adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are badly reported in clinical trials, and many rare and long-term ADRs cannot be detected in standard tests for efficacy. This makes systematic reviews of specific ADRs associated with a drug difficult to perform, and the sensivity and precision of searches can be poor if methods used to find efficacy studies are used.

Golder et al1 have published an excellent evidence-based best practice for systematic reviews of ADRs in the literature, from question formulation, to search strategies and database choices, to use of unpublished sources of data (such as spontaneous data and theses). Essential reading if you are involved in the search for harms, and want to avoid false negatives…

-

Overview: comprehensive and carefully constructed strategies are required when conducting searches for adverse effects data Golder, Su et al. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, Volume 113, 36 - 43 ↩

Dynamic to static

Back in 2000, before social media1, my first website was a simple set of static webpages about adverse drug reactions. In 2003, as the then blogosphere expanded, I integrated Blogger into the site. Later, I moved to the more complex Movable Type, before finally settling on Wordpress.

Wordpress has been great. It’s fantastic blogging software, but it is high maintenance. Constant updates are required, and the high usage of Wordpress mean it is under constant attack by hackers. After multiple hacking attacks, the last of which injected spam into 16 years worth of posts, I’ve moved back to a static website using the Marie Kondo of blogging, Jekyll, as a generator, with the standard minima theme. It’s not as convenient as Wordpress, but the benefits of low maintenance and having to learn new skills (like Markdown) far outweigh that.

-

In 2019, it is very much after social media. ↩

Medicines Safety Week – Make a pledge, make a habit.

It’s medicines safety week this week, and medicines continue to be an avoidable harm of modern healthcare. Modern pharmacovigilance stems from the birth defects arising from the use of thalidomide, but despite improvements in pharmacovigilance new issues arise with both new medicines and ancient medicines. Some issues with well established drugs can rumble on for years before effective action is taken.

It’s medicines safety week this week, and medicines continue to be an avoidable harm of modern healthcare. Modern pharmacovigilance stems from the birth defects arising from the use of thalidomide, but despite improvements in pharmacovigilance new issues arise with both new medicines and ancient medicines. Some issues with well established drugs can rumble on for years before effective action is taken.

A useful update on your knowledge of adverse drug reactions and how harms can be reduced can be found at the BMJ written by Ferner and McGettigan.

One meaningful outcome of this week, should be a commitment to improving medicines safety by reporting an adverse drug reaction to regulatory authorities by the end of the year. Do it before the leaf turns, and when the leaf has turned make it a habit of your practice.

Only by pooling our efforts can we improve medicines safety, and each report contributes to detecting and dealing with the safety issues that cause. In the UK, you can report via the Yellow Card Scheme if you are a patient or healthcare professional, but if you aren’t based in the UK there will be a system for you.

The picture at the top of this post is from the Uppsala Monitoring Centre, who are running an excellent social media campaign to raise awareness globally along with regulatory bodies around the world.