Human Factors Teaching: Using storytelling.

A few years ago I set up a small group teaching session for pharmacy students based around a fatal adverse drug reaction, using a video developed by the World Health Organisation. This year it is an inter-professional education event run by pharmacy and nursing academics. Sadly it will be taking place over Zoom, rather in the building you can see above, but that has made timetabling an inter-professional event easier than normal.

In the past I have used the event to discuss both technical and communication issues that led to the patient’s death, and for the impact the video has on first year students to raise the issues of harm in clinical practice. While revising the preparatory material, I decided to make it less technically focused, and more focused on the impact of the event and team communications. I’ve also given some limited pre-reading to enable a better understanding of the video dramatisation they are going to watch. It’s written in a less academic style than I normally use, based more around story telling. Here is the text I wrote for the teaching session, just in case it is of interest to people. For those who want an in-depth look at the case involved, you can read the Toft Report here in PDF format.

Just an Ordinary Day

Every day thousands of healthcare professionals go to work.

To earn a living. To make a difference. To help people.

And every day healthcare professionals are involved in incidents that lead to patient harm, and in some cases deaths.

With very rare exceptions, none of them went to work to do this.

Here is a story.

In the 1960s, a team of scientists at Eli Lilly in the US investigated a naturally occurring chemical from the rosy periwinkle plant. The chemical was called vincristine, and they tried to use it to treat diabetes.

A press photo circa 1961 showing some members of Eli Lilly’s vincristine research team By Crossgates - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0.

It didn’t work.

But it did cause myelosuppression (suppression of the bone marrow’s ability to produce blood cells).

They tested it in leukaemia.

It worked.

Vincristine became a key drug in many cancer regimes. Its use in leukaemia and lymphoma has saved many lives.

Fast forward to 2001

A 18 year old boy in Nottingham had successfully been treated for lymphoblastic leukaemia. He was in remission, and in the maintenance phase of his chemotherapy. This consisted of intravenous vincristine and intrathecal (into the spinal fluid) cytosine every three months.

Wayne Jowett had been under treatment for 2 years, but he was out of the other end. His treatment had given him a future.

But a terrible mistake would take all this from him.

On the 5th of January 2001 a doctor would inject vincristine into Wayne Jowett’s spine. The vincristine worked its way up his spine progressively paralysing him. He spent the rest of his life on paediatric intensive care, dying on the 2nd of February 2001.

The doctor was charged and convicted with manslaughter, but there were multiple failings at the hospital that led to this incident. This was not the mistake of one person.

Mistakes are rarely caused by the solely by the actions of one person. Systems of work, the way we communicate with each other, the design of equipment we use can all conspire to put those at the point of care in unsafe positions which can can harm those we seek to care for.

Like Wayne Jowett.

The session

This session will use a World Health Organisation dramatised case similar to that of Wayne Jowett to highlight how such errors can occur. Together you will explore how the event happened, and how things could be improved to avoid such events in future. The specifics of the drugs matter less, than how the mistake arose.

What you need to do

During the session you will watch a video of the dramatised event. You can use this document to help you analyse the events (read it before the session). Use a scrap of paper to jot things down to avoid using your computer.

You will then work as a mixed group of nursing and pharmacy students to look at the event, to find all the contributory factors that led to this event, and to look at the team working between the various professionals in dramatisation. This is a great opportunity to see different perspectives on each others professions as depicted in the video, and to learn from each other.

In order to protect each other, yourselves, and your patients from future errors.

Electronic prescribing: Different professions, similar problems.

Our research group has a new paper (Open Access) looking at the experiences of multi-professional prescribers using an electronic prescribing system. We suspected some differences between the professional groups (nurses, pharmacists, and doctors), but they all reported similar experiences. The pharmacists had some differing perspectives because of their monitoring role in prescribing, but their own experiences matched those of the other professions. Not entirely unexpected given what we know about human cognitive bias.

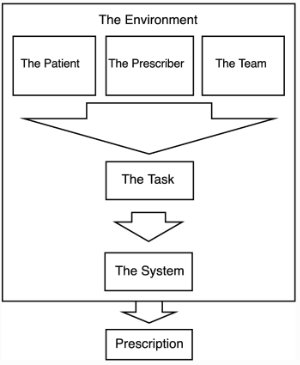

We present an analysis of six major interacting themes involved in the production of a prescription. Many of these echo areas found in other studies.

We conclude that:

Medical and non-medical prescribers have similar experience of prescribing errors when using CPOE, with the broad areas of concern aligned with existing published literature about medical prescribing. Causes of electronic prescribing errors are multifactorial in nature and prescribers describe how factors interact to create the conditions errors. Solutions focused on a single factor, such as system design or training, may only result in only limited impact on prescribing errors. While interventions should focus on direct CPOE issues, such as training and design, socio-technical and environmental aspects of practice remain important.

Alshahrani, F., Marriott, J.F. & Cox, A.R. A qualitative study of prescribing errors among multi-professional prescribers within an e-prescribing system. Int J Clin Pharm (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01192-0

Photo by National Cancer Institute

Medicines Safety Week: Special Medication Safety Edition of the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice

Over the past year I’ve been working on a Special Edition of the International Journal of Pharmacy Practice on focused on medication safety with some colleagues from Cardiff University. It’s been a long haul, but we have just got it out for medication safety week 2020. It has been an interesting process of filtering and reviewing papers, but I think we have an interesting mix of papers, that fit around the WHO’s global patient safety challenge.

We also have an editorial in the issue, which gives a whistle stop tour of the papers and how they fit with the WHO framework. It concludes as follows.

This Safety edition illustrates the breadth and diversity of pharmacist involvement in research on patient safety from an international perspective. A recent report from the International Pharmaceutical Federation (FIP) entitled Pharmacists’ role in ‘Medication without harm’ summarises the evidence base for pharmacists’ contributions to patient and medication safety and concludes that ‘all pharmacists may consider themselves as medication safety pharmacists — advocates for safety within the healthcare system and for each individual patient’. The contributions in the Medication Safety Special Edition aim to add positively to the evidence base for medication safety, and we hope that the increasingly important role of pharmacists in medication safety and related research is demonstrated by the range of papers included from around the world.

Medicines Safety Week: Finding Needles in Haystacks

It’s Medicines Safety week. The twitter hashtag #medsafetyweek shows a lot of international activity to encourage awareness of the harms of medicines, with a special emphasis on the importance of everybody playing their part in reporting suspected side effects of medicines. Every report counts.

The MHRA’s Yellow Card Scheme has been established since 1964 and has just reached the milestone of having a million reports submitted. When you make a single report, you might think it won’t have great impact, but it can. The MHRA as part of today’s celebrations have highlighted the case of a single patient reporting, leading to a change in medicine information. I think this sort of story telling about the reporting of side effects is so important to encourage further reporting. It’s great to see the MHRA doing this.

However, it isn’t the only story. You might think once an individual report of a suspected side effect has been analysed, it just disappears into the haystack of reports where we are looking for those valuable needles. However, because of the way in which we find side effects in databases such as the Yellow Card Scheme, through signals of disproportionality, every existing card also helps find side effects from new reports that are submitted.

Disproportionality analysis is primarily a tool to generate hypotheses on possible causal relations between drugs and adverse effects, to be followed up by clinical assessment of the underlying individual case reports. It is based on the contrast between observed and expected numbers of reports, for any given combination of drug and adverse event.

Unlike trying to find a needle in a haystack, where the haystack is in the way, finding an adverse effect in a database requires the haystack of previously submitted reports to find a possible link between a drug and a side effect.

Those million reports continue to serve a purpose.

Every report counts. Twice.

Photograph: Photo by Idella Maeland

World Patient Safety Day

It’s patient safety day. If you go to twitter and look at the hashtag #WorldPatientSafetyDay there’s lots of interesting and valuable material that can be used to make healthcare a safer place for both patients and healthcare staff.

But there is one easy small thing you can do to have huge impact.

This year make a commitment to spend 5 minutes on one thing that adds to global patient safety.

You can definitely do it if you are a health professional.

You might be able to do it if you are a patient or a carer, but I hope you don’t need to.

You can report a suspected adverse reaction (side effect) to your country’s regulatory system.

We don’t know much about the real-world safety of new drugs and vaccines when they first come to market. We can predict what might happen from the studies that got the drug or vaccine licensed, but when they are used in the wider population new side effects might become apparent. Sometimes even mild side effects may be indicative of a more serious issue in other patients.

Therefore every report of suspected adverse drug reactions that regulators receives adds a little knowledge. That knowledge accumulates. And over time that aggregation of data can give a signal of possible harm. And that helps regulators keep us all safe by focusing where they need to look.

So if you take a medicine or a vaccine this year, please let regulators know if you suffer a side effect.

You probably won’t.

You might even think the side effect is from something else. But you only have to suspect, not be sure. And each one helps other patients by ensuring we know a drug or vaccine is safe, or alternatively allowing us to find a problem that can be prevented in others.

If you are a health professional, just reporting one of the many suspected adverse drug reactions you see a year will make you better than average reporter.

And it will take you 5 minutes.

Once a year.

Photograph: Photo by James Yarema