Principles and Practice of Pharmacovigilance and Drug Safety

I am pleased to annouce the publication of a new textbook ‘Principles and Practice of Pharmacovigilance and Drug Safety’. It is an edited volume with over 50 expert authors with an international reach, with each chapter peer-reviewed.

The science of drug safety and pharmacovigilance has rapidly evolved in the 21st century. The knowledge and principles it contains are of increasing importance in clinical and practice settings. The aim of this book is to deal with the gap in knowledge about pharmacovigilance and drug safety, including the application of pharmacovigilance knowledge to individual patient cases in clinical practice.

A holistic approach is taken with each chapter written from the perspective of a practitioner, industry personnel, researcher, or regulator, creating a synergy between drug safety, pharmacovigilance, and clinical practice. Chapters offer key material on adverse drug reactions, medication errors, prescribing safety, pharmacovigilance as well as data sources used in drug safety and pharmacovigilance. Each chapter is structured as a self-contained learning resource, with learning objectives, and worked cases.

The book is suitable for undergraduate healthcare professions, postgraduate students, researchers, clinical practitioners – including those with prescribing responsibilities. It will also be useful for professionals moving from a clinical practice role to a specialist pharmacovigilance role. For those already in a pharmacovigilance role, the book offers insight into the theory and practice of drug safety and pharmacovigilance in clinical settings.

The seed of this project was planted 4 years ago, when in the midst of the pandemic in August 2020, Jimmy Jose contacted me with his ideas about creating a new textbook in the area of pharmacovigilance. We both had similar views on trying to create something that straddled the regulatory, scientific, and clinical practice. Co-ordinating such an endeavour was a massive under-taking, and we were grateful to have a third editor join us, Vibhu Paudyal. I hope we have succeeded in creating what we intended, and I thank the international authors for their hard work.

The two chapters I contributed to are:

van Hunsel, F., Younus, M.M., Cox, A.R. (2024). Patient and Public Involvement in Pharmacovigilance. In: Jose, J., Cox, A.R., Paudyal, V. (eds) Principles and Practice of Pharmacovigilance and Drug Safety. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51089-2_12

Jose, J., Cox, A.R., Bate, A. (2024). Introduction to Drug Safety and Pharmacovigilance. In: Jose, J., Cox, A.R., Paudyal, V. (eds) Principles and Practice of Pharmacovigilance and Drug Safety. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-51089-2_1

Vaccine boost

Yet again, a new phase of the pandemic in the UK. First there was the prodrome of general awareness of a new virus in China, with the uncertainties, and false re-assurances, evaporating away to leave the reality of the first wave. Deaths. Lockdowns. New uncertainties. How does it spread? Should I wash my shopping? Should we wear masks? The answer to the latter I found was no — I was refused access to a blood donation centre because I declined to take my mask off.

Cases fell, and second phase arrived. A summer of ‘eat out, help out’ commenced, when you could nervously try the new normal. I watched Tenet in two masks — they were required in the newly opened cinemas. I ate breakfast in a hotel with ineffective plastic screens between tables. It felt like the eye of a storm passing, and, to some, the storm receding. It hadn’t.

Phase 3. A gradual worsening, some due to our prior help at eating out, the arrival of Delta, and the shaft of light of vaccines. A battle between vaccination and the virus, with many deaths. A cold, dark lockdown. Then a summer of confidence courtesy of science. The fourth phase has been an uneasy accommodation with SARS-COV-2, with high cases, and lower deaths. The virus is not yet endemic, but arguments are. Worse case predictions, post freedom day, were thankfully wrong.

Now we have the fifth phase. A new variant (Omicron) has arrived, sufficiently different to Delta to raise concerns about possible reduced effectiveness of the vaccines, with a potentially far higher level of transmission. Cases in South Africa have rapidly increased, and UK cases appear to be rising (134 today). There is not enough data to make any strong claims about whether it is mild or severe.

This time it is a race between boosters and a possible Omicron wave of unknown potential to cause harm. The UK target is to give 25 million doses before the end of January, to raise the wall of vaccine-induced immunity to minimise the potential harms from this round of uncertainties. Liz Breen and I have an article assessing if this target can be met at The Conversation. We are optimistic on that front.

The key ingredients for a successful booster programme have thus been promised – vaccine stock, vaccination sites and staff resources. If they can be made available in a timely fashion, then replicating the vaccination drive of the first half of 2021 is possible – as is meeting the government’s January target. Encouragingly, vaccination rates were already improving before these changes

Everything else is up in the air, and the gradual clarity on Omicron over the next few weeks will tell us whether this phase is an easy or a hard one. Until then, this comment from a Bloomberg article — that has been shared widely as evidence Omicron is mild — is probably a good default position to hold.

“The only ones putting their hand on their hearts and telling the world don’t worry, this is going to be mild, haven’t learned enough humility yet in the face of this virus.”

Photo from Fusion Medical Animation

Talking about vaccines

I recently appeared on the Uppsala Monitoring Centre podcast Drug Safety Matters on the subject of talking about vaccine safety.

With vaccine hesitancy on the rise and misinformation spreading like wildfire on social media, drug safety specialists may have a hard time knowing how to talk about side effects without affecting people’s trust in vaccinations. Anthony Cox from the University of Birmingham and Daniel Salmon from the Institute for Vaccine Safety share their best advice for balanced and responsible vaccine safety communication.

Tune in to find out:

- Why we can’t allow bad actors to damage the drive for openness in research and data

- Why we should be open about uncertainty and always frame risks in the context of benefits

- How to prevent public health advocacy from biasing the science of vaccine safety

Photo from CDC

Communicating Vaccine Safety

Just a short post linking to an article about communicating vaccine safety, which I contributed to, at Uppsala Reports. Here is an excerpt.

We can’t allow bad actors to damage the drive for openness in research and data,” Cox says. Science is about finding the closest approximation to the truth, he explains, and it is essential that we have open discussions about what that is. Trying to control, hide, or bias the truth will only generate distrust in authorities.

Dr Daniel Salmon, director of the Institute for Vaccine Safety at Johns Hopkins School of Public Health in the US, agrees that the risks and benefits of vaccines must be discussed with honesty and objectivity.

“Vaccines are such an impactful medical and public health intervention, and we have to be careful not to fall into the trap of overselling their value or underselling their risks,” he explains. “If we overstate the benefits, we run the risk of losing people’s trust in the science and system.”

Blood clot fears: how misapplication of the precautionary principle may undermine public trust in vaccines.

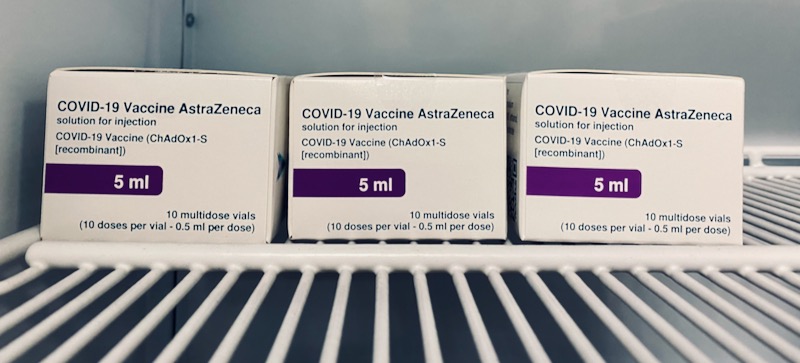

The arrival of effective vaccines against COVID-19 has been one of the few good news stories of the pandemic. However, communicating the safety of vaccines has long been difficult, as shown by most countries having some level of vaccine hesitancy, including hesitancy towards COVID-19 vaccines specifically.

Just as regulatory authorities – such as the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) – had systems in place to assess if the vaccines worked, so too did they create carefully thought through vaccine safety plans to deal with any safety signals arising after the vaccines’ deployment.

However, this week the EU’s plan for vaccine safety was thrown into confusion. At least 12 EU states have suspended use of the AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine because of concerns of a possible link between the vaccine and blood clots. These concerns are registered in spontaneous reports, where a patient or healthcare professional suspects a link between an adverse event they’ve witnessed and the vaccine. Reporters do not have to be sure of a link, and these reports do not prove there’s any association between the vaccine and the event.

The number of blood clots reported among people taking the vaccine, assuming even a fairly high level of under-reporting, does not seem to be higher than would be expected in the general population. Many things happen after vaccination that would have happened without the vaccine.

That said, in some countries, such as Norway and Germany, an extremely rare form of blood clot in the brain called cerebral venous sinus thrombosis (CVST) has been reported. Incidence of CVST in the normal population is hard to measure, although Johns Hopkins Medicine has said it may affect around one in every 200,000 people each year. In Germany, the incidence of CVST post vaccination has exceeded this rate, so the EMA is carefully examining each case to look for possible contributing factors.

But so far, the World Health Organization, EMA, MHRA and AstraZeneca have all said that there is no evidence of a causal link between the vaccine and clots, and the EMA has said it is firmly convinced that the benefits of the vaccine far outweigh the risks. Yet if this is the case, why have the advisory committees of some EU states decided to suspend the vaccine?

A good tool badly used

A major reason appears to be the misapplication of the precautionary principle. This is where you take anticipatory action to avoid potential harm, even when the evidence around that harm is uncertain. It can be a useful tool when needing to make a decision in a situation that includes risk and uncertainty.

The precautionary principle evolved from critiques of risk assessments that were based on scientific methods. These, it was argued, were too conservative, requiring too much evidence to prove risk, and so perhaps biased towards seeing an absence of harms.

The earliest forms of the principle are thought to have arisen in West Germany in the 1970s, where “Vorsorgeprinzip” was used in environmental policy to limit actions that were suspected but not proven to cause ecological damage. Past case studies of harms for which there were early warnings but only later actual evidence – such as asbestos – show the sorts of outcomes that the principle can potentially help avoid.

Regarding pausing the AstraZeneca vaccine, the principle has been cited explicitly by some EU states. Others have invoked it implicitly in interviews, saying they will “err on the side of caution”. However, there are trade-offs – and that’s the primary reason why we can say the principle has been misapplied.

COVID-19 vaccines are being used to prevent deaths. Decisions to suspend their use will slow vaccination campaigns by reducing vaccine availability. Suspensions might also affect vaccine uptake by sparking wider concerns about safety among the public. Confidence in the AstraZeneca vaccine is already relatively low in Europe, with high-profile comments about its effectiveness having dented uptake.

So rather than avoiding risk, the principle has instead moved countries away from one risk (blood clots) towards another (lower vaccine coverage). The impact of the latter could be much larger.

Even if this weren’t the case, the principle has still, arguably, been misapplied. Plans for COVID-19 vaccine safety monitoring until now have been based around rigorous scientific evaluation of safety signals, careful communications to ensure vaccine hesitancy is not increased, and ensuring that signals are investigated to examine if any risk requires regulatory action.

Because potential safety signals arise often in vaccine and drug safety, with many being false signals, the precautionary principle doesn’t fit with such plans. It is too sensitive, and in the case of COVID-19 vaccines, doesn’t initiate any safety assessments that aren’t already happening.

As we have seen this week, misapplication of the precautionary principle leads to erratic decision making that fails to do the very thing it intends to: lower risk. The decisions made could potentially have long-term health effects both in the EU and globally. As a result, one might say we need to be more cautious about the application of the precautionary principle.

Post publication note

This article was first published at The Conversation on March 16th 2021. Since it was published the information about the risks associated with the AstraZeneca vaccine have become clearer, although the central argument of this piece still stands.